Read the original article here.

Human rights researcher Alexa Koenig said, “Visuals are often the bridge between lived experiences on the ground and some of the greatest seats of power,” but that was not what Ashley Funk thought would happen when she received her first camera at age six.

She took pictures of everything and over time, she became drawn to taking photos of nature around the small, rural, coal-country town she grew up in. One day she saw litter alongside the road and thought it wouldn’t be hard to clean up. So Ashley, together with a friend from high school, created a roadside clean-up crew to make Mt. Pleasant, Pennsylvania, more pleasant. Their crew became the first township approved “Adopt-a-Community” in the county to address a pollution problem visible to all.

But Ashley’s will to address our collective pollution problems did not stop there. Her grandfather died of black lung disease from working in western Pennsylvania’s coal mines. This loss, coupled with her concern about what age she would get cancer due to growing up playing on toxic waste piles, drove her to dive into research on the long-term effects of less visible pollutants.

Ashley’s immersive investigation into air pollutants opened her eyes to the work of then-NASA scientist, Dr. James Hansen. She studied his graphs indicating how much the climate was changing but how little our governments were doing about it. Her familiarity with Hansen’s work meant she also understood the urgency of climate change and the escalating impact of our insatiable craving for fossil fuels on basic human rights. In 2012, Ashley, then age 17, teamed up with other dedicated young people, to collectively take their case to the halls of justice and the court of public opinion.

With the support of Our Children’s Trust, Ashley filed a petition with five Pennsylvania agencies, asking them to adopt rules to reduce the state’s carbon dioxide emissions in line with the best science on climate recovery. That same day, Ashley sent her personal story—told through the short film, TRUST Pennsylvania —to over 200 state and federal decision-makers, along with a personal letter calling for action on emissions reductions.

In her film, Ashley explains, “When we do litter clean ups in our community, everyone drives by and they thank us and they appreciate what we are doing because they can see the improvement we are making. But, whenever our government imposes new regulations on the amount of greenhouse gases an industry can release in the atmosphere, most responses are negative because people can’t see how we are harming the atmosphere.” In an interview with National Public Radio, Ashley’s father corroborated her insight, sharing that part of the reason he didn’t believe in climate change was, “I can’t see it. I don’t believe it.”

Making the Invisible, Visible

Ashley’s observation supports what climate communications experts know well for human beings —seeing is believing. And since we cannot ‘see’ the slow and incremental, yet urgent and irreversible, degradation to our planet and basic rights, we seldom act.

Some initiatives aimed to change that. In 2005, Yale University launched its pioneering program on Climate Change Communication. In 2007, photographer James Balog founded the Extreme Ice Survey, and in 2016, Climate Visuals launched the world’s first evidence-based photography resource. By making climate change more visible and tangible, these efforts create shifts in public understanding and, ultimately, such shifts can have ripple effects in legislatures, offices of the executive branch, and courts.

Climate Visuals in the Courtroom

Although courts do not formally look outside the courtroom when rendering legal decisions, political scientists have long studied judges’ sensitivity and responsiveness to public opinion on important societal issues influenced by evolving norms and values. For example, in 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges, the U.S. Supreme Court legalized gay marriage throughout the country, after decades of social mobilization that culminated with increased public support of marriage equality. Given the position climate communications hold between media, public opinion and the law, these communications can foster broader awareness, education, and movement building, while serving as a cornerstone of strategic climate litigation.

To date, the majority of climate communications work has focused on helping the public understand how climate change is already affecting our lives. But the field of climate litigation still struggles with how visuals could improve courts’ understanding of their essential role in flattening the climate curve and curtailing the human rights violations coming from extractive industries.

When U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer was asked for his opinion on the breadth of the federal public trust doctrine, a key legal issue in a number of strategic climate cases including Juliana v. U.S., he responded, “I don’t know.” He explained that judges are “generalists” and must rely on legal scholars and practitioners to inform courts’ understanding of how to interpret and apply the law in relation to shifting global circumstances.

Justice Breyer’s response is a clear call to action. Tasked with the responsibility to convey the facts of a case clearly and link those facts to the law, climate litigators should consider the effective integration of visuals to strengthen cases and, in turn, secure justice and accountability for plaintiffs. The Indigenous community of Sinangoe in Ecuador and their legal team provide an inspiring illustration of how lawyers can answer this call to action and successfully leverage visual evidence in the courtroom to secure landmark legal rulings.

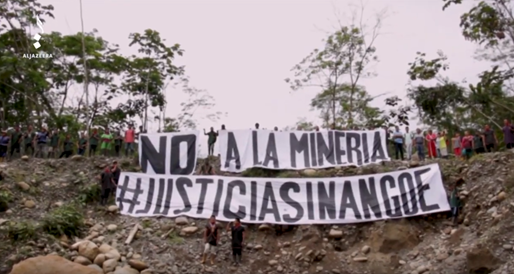

The high-Andean peaks of the Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve in Ecuador safeguard the headwaters of the majestic Aguarico River—a major tributary of the Amazon River—that is vital to dozens of Indigenous communities and the ancestral home of the Kofan people of Sinangoe. One day, the Kofan’s Indigenous Guard heard a low hum, and decided to fly a drone to investigate from afar. The drone captured images of illegal gold mining on the banks of the Aguarico River. Upon further investigation, the Kofan learned that the Ecuadorian government had essentially given away the headwaters of the river to the mining industry without notifying or consulting the community.

n the following months, the Indigenous Guard travelled to the remote site deep in Kofan territory and methodically collected video footage via phones and drones that showed polluted water, compacted soil, and destroyed forest. They then brought a lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government, integrating visual evidence. Their legal team coupled extensive phone and drone footage with satellite imagery and maps to compile robust evidence that no one could dismiss. Based on the full body of legal evidence, the court ruled in favor of the Kofan. The case culminated in the revocation of 52 mining concessions and set a landmark precedent for Indigenous people throughout the Amazon region.

As visual evidence galvanizes movements around the world and provides irrefutable evidence, climate litigators have an opportunity. By leveraging phone, drone, and satellite evidence in courts, it becomes possible to show what otherwise can’t be seen. Together, we can become a vanguard in the movement to take advantage of visual evidence to argue and persuade.

Kelly Matheson is a senior attorney and associate director who leads the Video as Evidence Program for the international human rights organization, WITNESS.

![Making the [In]Visible Powerful: Leveraging Climate Visuals in Courts](https://toamazonia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Matheson_Image-20-30-10-1200x679.jpg)